Rise and fall of Britain's largest mental asylum

By 1866, Lancashire’s three lunatic asylums at Prestwich, Rainhill and Lancaster but were full.

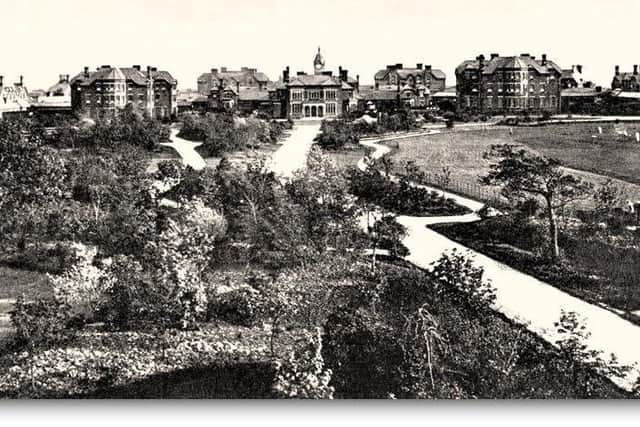

Plans were drawn up to build a fourth in the countryside north of Preston at Whittingham to meet the pressing demand for extra accommodation. The asylum, built from the red brick, so synonymous with Lancashire, officially opened its doors on April 1, 1873, although 115 patients had already been admitted a year earlier, many of whom originated from Victorian workhouses.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe hospital played a pivotal and early role in the development of electroencephalogram (EEG) in the fields of psychology and psychiatry. EEG is the recording of brain activity. It is tested when small sensors are attached to the scalp in order to pick up the electrical signals produced when brain cells send messages to each other.

The building lacked aesthetic beauty but was architecturally imposing. Once the main building was constructed the site started to grow as buildings were steadily added as demand rose.

The annex, also known as St John’s division, was the next to be drafted in after the purchase of 68 acres of land. This was completed in 1880 and accommodated 115 patients. As demand grew so did the facility and four more buildings were put up, one of which was to become the most prominent landmark, the clock tower. It was soon lost to history, though, as it was taken down in 1914, prior to the First World War.

By this time there were 2,820 inmates – more than double the asylum’s original capacity. Whittingham became a military hospital during the days of the First World War and a significant change was made. Committee records show it was at this moment Whittingham Asylum transformed into Whittingham Mental Hospital, a breakthrough which was considered a success as a more modernised approach followed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy its heyday the site boasted its own railway, a church, farms, telephone exchange, post office, reservoir, gas works, brewery, orchestra, brass band, ballroom and butchers. In 1929 an ‘open door’ process was introduced which meant all wards were unlocked, which in principle meant the whole hospital was unlocked for people to come in and be looked after.

The Second World War was instrumental in the growth of Whittingham Mental Hospital. The facility again served as a military hospital and the patient population reached its peak at 3,553, making it the biggest mental hospital in Britain and one of the largest in Europe. The end of the war signalled the start of Whittingham’s decline. Once a Victorian dream, the mental hospital was fast becoming redundant as new approaches to mental health care were adopted.

By the late 1960s, there was a growing chorus of concern, led by student nurses working there, about conditions in the century old facility and standard of treatments of patients.

Lawrence Butterfield, a former worker at the asylum, referenced the dire conditions during the 1970s in his book, ‘Sticks and Stones’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe wrote, “Whittingham was outdated in every single way possible and looked like something out of a Gothic horror film. It typified the old Victorian asylum.”

A top level inquiry was launched by the government into Whittingham, headed by Sir Robert Payne, and the subsequent report published in 1972 made for damning reading.

It shone light upon mistreatment, poor operations and fraud, which plagued the site. There was clear discontent from student nurses for many years after it is

alleged that they perceived widespread malpractices, in turn leading to the student nurses getting together and voicing their concerns about the issues they were facing but these were, at first,

dismissed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe main findings of the inquiry revolved around ill treatment, poor practice and financial mismanagement. The mistreatment of patients was mainly linked to four wards, all located within the St Luke’s division of the building. It was alleged violence and cruel acts were committed by members of staff against patients which included: patients being dragged across the floor by their hair and being punched and assaulted before being locked in a room under the stairs in all different temperatures.

The worst identified punishment was dubbed the ‘wet towel’ treatment in which a wet towel was twisted around the neck of the victim until they fell unconscious.

The mistreatment was horrific, but the conditions and facilities were judged to be similarly bad. While wards were chronically short-staffed, the buildings were poorly maintained and some wards were infested with cockroaches. The

financial mismanagement was also a problem. Patients were stolen from regularly – a fact highlighted by an audit of 1968-69 accounts which revealed £91,000 was issued to patients but only £42,000 was returned via the on-site shops.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Michael McKeown, reader in democratic mental health at UCLan explains: “Whittingham had a bad press in the late 60s and early 70s with a public inquiry into abuses. Then there were concerted efforts to improve services and the image of the hospital before its eventual closure.”

Brutality, dishonesty, muddle and abuse were words described about the asylum following the report. A nurse was convicted of manslaughter of a patient on the site, which led to calls for all members of the Whittingham Hospitals Management Committee to resign.

Regarding the wet towel treatment, Lawrence Butterfield said: “The allegations of wet towels being used to abuse the patients at Whittingham only fuelled the long-standing myths of wet towel treatment being a norm within psychiatric establishments. Rumours and gossip were rife about its dreaded past.”

Due to advances in the medical treatment available to deal with mental health issues, the introduction of the Mental Health Act 1960 and the huge costs associated with keeping a site of that magnitude open, it became inevitable the hospital was going to close down. By 1995 the last of the long-stay

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Adpatients were returned to the community and the facility shut its doors for good.

* With thanks to Phil Knapman for images.

Whittingham Lives Project Scheme

The University of Central Lancashire is supporting Whittingham Lives, a two-year multi-faceted arts and heritage project aimed at researching, exploring, celebrating and maybe critically reviewing the culture and legacy of Whittingham Asylum.

The venture strives to piece together the lives of those who lived, worked or were treated at Whittingham Asylum.

The main aim of the project is to preserve for future generations a comprehensive record of history, culture and achievements of Whittingham Asylum.

Researchers are

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Adappealing for those who have memories of the 150-year-old mental asylum. They have received nearly £70,000 from the British Heritage Lottery fund and the Arts Council to preserve memories of those associated with the asylum.

Dr Mick McKeown, who is supporting the project on behalf of UCLan, said: “ We at UCLan could see right away how a project like Whittingham Lives is highly relevant to our teaching and research work in mental health and would be a great way to bring the university more into the community and vice versa.

“We are all looking forward to being part of such a big project and hope we can do justice to its aims. The way in which communities think about and care for people with mental health problems is a major issue for our times, and we hope to make a positive contribution by learning the lessons of the past and engaging people in the present in informative and enjoyable activities and events.”

Researchers are looking to develop material in five strands: digital, historical, literary, musical and visual.

* To get involved with the Whittingham Lives project email [email protected] or visit www.whittinghamlives.org.uk